Grippy Socks Jail: Build a Life Worth Living

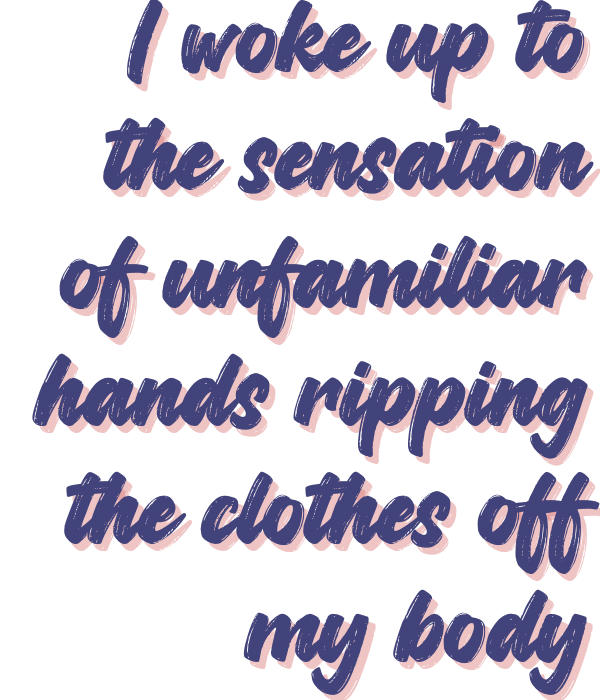

I woke up to the sensation of strange hands ripping the clothes off my body. Struggling to make sense of my surroundings, I quickly realized the futility of this endeavor without access to my glasses. Lying on the hospital gurney, I could only see the bright, hot examination lights. As the fear and confusion grew, an animal instinct in my foggy brain urged me to resist. However, my efforts proved fruitless, as the sedative effects of the sleeping pills took hold, and I struggled to regain control of any motor function. I could only manage nonsensical, slurred speech, flailing about the bed like a crazy homeless drunk. As I tried to sit up, the hospital staff surrounded me and tied my hands and feet to the bed. The last thing I remember was them shoving the big plastic tube down my throat.

I woke up to the sensation of strange hands ripping the clothes off my body. Struggling to make sense of my surroundings, I quickly realized the futility of this endeavor without access to my glasses. Lying on the hospital gurney, I could only see the bright, hot examination lights. As the fear and confusion grew, an animal instinct in my foggy brain urged me to resist. However, my efforts proved fruitless, as the sedative effects of the sleeping pills took hold, and I struggled to regain control of any motor function. I could only manage nonsensical, slurred speech, flailing about the bed like a crazy homeless drunk. As I tried to sit up, the hospital staff surrounded me and tied my hands and feet to the bed. The last thing I remember was them shoving the big plastic tube down my throat.

It was the fall of 1997. I was a single woman in my 20s & had only recently finished my bachelors. After some struggle, I found a decent-paying job and saved enough to buy my first home. On the surface, everything seemed fine. People told me: “I should be proud” of my accomplishments. In addition, I felt grateful for the financial stability and the fact that I owned a home at just 27. To begin with, I removed myself from an abusive relationship and got my life back on track. At that time, my main priorities were remodeling my home. I was preparing an empty unit in my duplex for new tenants moving in at the start of the school year.

It was the fall of 1997. I was a single woman in my 20s & had only recently finished my bachelors. After some struggle, I found a decent-paying job and saved enough to buy my first home. On the surface, everything seemed fine. People told me: “I should be proud” of my accomplishments. In addition, I felt grateful for the financial stability and the fact that I owned a home at just 27. To begin with, I removed myself from an abusive relationship and got my life back on track. At that time, my main priorities were remodeling my home. I was preparing an empty unit in my duplex for new tenants moving in at the start of the school year.

I felt helpless and utterly defeated in my attempts to establish a social life. Initially, I briefly tried dating and placed an ad in the city’s local newspaper (this was long before online dating) As you might guess it didn’t go well.. Frustrated and disheartened, I quickly gave up, took down the ad, and resigned myself to the idea of becoming an old cat lady.

At the time, the show Friends was hugely popular. I entertained the thought of building a friend group like that. However, the idea only left me feeling sad. I reminded myself how unprepared I was to make such connections. Memories of childhood bullying and ostracism replayed in my mind. These memories acted as fuel for a growing sense of inadequacy. Desperately, I asked myself, “Why does nobody ever like me”!”

Unfortunately, I was still decades away from understanding the answer, which would eventually come with my autism diagnosis. For now, all I could do was sit with the sadness, overwhelmed by self-pity and hopelessness.

As time progressed steadily forward, I struggled to keep my head above water. Efforts to push these negative thoughts out of my mind proved futile. As the weight of isolation grew heavier, my depression began to intensify. Determined to “make friends, ” I challenged myself to join various activities or groups in the area. However, I always backed out at the last minute. Panic would take over, paralyzing me. I was never able to take that first step.

Ultimately, I simply did not understand what made “me different.” Without the autism diagnosis, the only explanatiuon I could compe up with is “I am a weirdo”. It has only recently occurred to me that my feelings of shame were never isolated experiences in response to a specific faux pas. Instead, it was a constant, pervasive undercurrent in life.

In the end, the social world, was always an inherently scary place. I was never allowed to understand what was wrong with me. I only knew it was something inexplicbly horrific and painfully obvious to everyone but me. I just had to accept this as fact. To ask the question is a matter of stupidity. No matter how hard I tried, the nature of my supposed inherent wrongness always remained out of reach.

By the time I reached adulthood, I gave up trying to unterstand. I had fully internalized this “wrongness” as an undeniable truth. Consequently, a ticking time bomb lurked within — this complete absence of anything resembling a sense of self— & remained unnoticed by everyone.

As I stewed in my own self-loathing, I attuned myself obsessively to any indicators that shame “might be imminent” – a process described as a “pervasive and affective attunement” (Doleza”, 2022, p. 740). The mental gymnastics involved in this constant vigilance were both overwhelming and exhausting. Part of me fixated on curating the perfect social mask, while another part scrutinized my every move, watching for anything that might cause others to dislike me (Holmes, 2015). This unique form of emotional self-sabotage is common among autistics. In my case, it made the idea of entering the social world terrifying and often left me frozen in fear.

As I stewed in my own self-loathing, I attuned myself obsessively to any indicators that shame “might be imminent” – a process described as a “pervasive and affective attunement” (Doleza”, 2022, p. 740). The mental gymnastics involved in this constant vigilance were both overwhelming and exhausting. Part of me fixated on curating the perfect social mask, while another part scrutinized my every move, watching for anything that might cause others to dislike me (Holmes, 2015). This unique form of emotional self-sabotage is common among autistics. In my case, it made the idea of entering the social world terrifying and often left me frozen in fear.As best as I can recall now, life unfolded uneventfully—or at least it seemed that way on the surface. My memories of the months leading up to my suicide attempt remain hazy. My memories remain clouded by dissociation, which shielded me from the pain of remembering. What I do recall is that life was filled with the monotony of loneliness, made slightly more bearable by my well-maintained daily routine.

-

Looking back, as an undiagnosed autistic, I knew there was always something different about me, that I couldn’t put my finger on. All I knew is that people didn’t like me because of it.

-

I constantly lived in a state of panic, terrified that others would latch onto some extraneous trait—something unrelated to who I truly was—and use it as justification to ridicule me.

-

I now understand that my fear and anticipation of shame reflected the normative standard by which I felt judged, growing up in a family of undiagnosed autistics successful masking was an unbreakable cardinal rule.

-

without AN understanding of the sociopolitical traumas that are inherent in the lives of autistic people, my daily social life was filled with interactions that carried the potential of shame.

-

With 20/20 hindsight I realize that stigmatizing shame has had an insidious impact on my life. Its purpose seemed to be tI’veghlight my failure to mask horrendously. What ItI’veghlightarned is that this form of stigmatizing I’vee is often deployed against entire groups simply based on their identity (Harris-Perry, 2011).

I found the perfect comfy spot on my living room sofa and prepared for an eternal slumber. I simply lookedd forward to the pain to end:

There’s no end to the pain, “I thought to myself.”

“I CAN’T DO THIS ALL BY MYSELF,” I REASONED.

These “seemingly” rational thoughts loomed in my mind as I headed toward a nearby Walgreens to pick up a bottle of sleeping pills.

After I managed to swallow the full bottle, my mind floated away into a hazy dreamland as my body grew limp. A short time later, I jolted awake to banging on my door. Angry that someone interrupted my well-laid plans, I tried to gather my thoughts. As I looked down at the receiver in my lap, I began to recall a hazy conversation with my concerned sister, who I assumed had called 911.

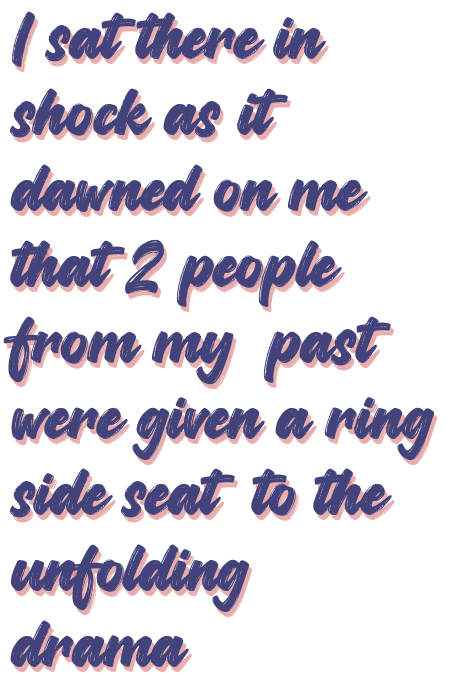

An emergency crew had managed to break open the door to my old Victorian home. In that moment, I became enraged with myself for not having fixed that old door latch sooner. As I stood up and stumbled toward my bedroom, a crew of emergency responders walked in, including my old college roommate (a cop) and a former high school classmate (an EMT).

Dumbfounded that two people from my past had a front-row seat to the unfolding drama, I started crying uncontrollably. My mind flooded with painful memories as I spiraled deeper into negativity. “Maybe they’re right… I am the problem,” I thought. I felt so overwhelmed with emotion that I couldn’t articulate anything. My body began to shake, and I shut down, becoming mute. With no will to fight, I was left to watch as events unfolded around me.

OVERCOME WITH SHAME, I THOUGHT, “GOD IS A KID WITH AN ANT FARM, AND HE’S SHINING HIS MAGNIFYING GLASS RIGHT ON ME.”

Alone in my bedroom with my old college roommate, I covered my head with a pillow as she attempted to convey something resembling empathy. Her clueless and pathetic gaze angered me beyond words as the barrage of stupid questions started. I wanted nothing more than for the ground to swallow me whole. I stumbled toward the bathroom to escape, but didn’t get far before my old roommate grabbed me by the arm. She sat beside me on the bed and insisted on getting more information from me.

-

-

Why don’t you tell me why you decided to do this?

-

I can appreciate that you don’t want to talk about it, but I can’t help if I don’t know what is going on.

-

“A friend of yours was concerned about you and wanted us to check up on you. Did you take this bottle of pills?

-

The questioning dragged on for what felt like an eternity. I sat silently, ignoring the questions and reflecting on our last conversation. Hope filled me as a new college freshman, grateful for the chance to leave my hometown behind. But life didn’t unfold the way I had imagined. My roommate, however, accomplished everything she aimed for. She earned her criminal justice degree, became a cop, and married her college boyfriend. Her normalcy became a cruel reminder of my own failures, and I started to despise her for it. A lump rose in my throat as I realized my life had become a reflection of my worst fears.

REALLY AM A WALKING SHIT MAGNET,” I THOUGHT BITTERLY.

After about ten minutes of this, my old roommate informed me of her plan to take me to the hospital. Blind panic surged through me as I remembered my old high school classmate—now an EMT—waiting in the next room.

“I CAN’T LET HIM SEE ME LIKE THIS!” I THOUGHT, MY MIND SPIRALING INTO CHAOTIC MEMORIES OF CHILDHOOD BULLYING.

“PLEASE, JUST LET ME PRETEND THIS IS ALL A NIGHTMARE!” I BEGGED SILENTLY.

In that moment, my mind yanked me back to freshman year, hiding in the girls’ locker room to escape the daily torture of the lunchroom. Only after he agreed to leave and let a coworker take over did I finally step out of my bedroom and allow myself to be escorted to the hospital.

Pushing those thoughts aside, I started feeling around for my glasses, only to realize my hands and legs were tied down. A nurse approached my bedside, working quietly. I politely asked for my glasses. She ignored me and sat across from me, scribbling notes in my chart. I repeated myself louder and louder, but she continued to ignore me. In that moment, I wondered what I had done to anger her.

As my mind slowly came back online, I began piecing together the events of that evening. I recalled hospital staff hovering over me just hours earlier, talking about me as though I didn’t exist. While they stripped off my clothes and pinned me down, panic took over as they tied my arms and legs to the bed. One male nurse stood out. He called me “another pathetic and crazy loser just seeking attention,” unaware that I was alert enough to process his words.

Then, I remembered the kind doctor who stepped in during that moment of horrific isolation. He told the male nurse to assist someone else, placed his hand on my shoulder, and met my eyes while sitting at my level. His kind eyes and sincere voice showed that he genuinely cared. He asked how I was doing, listened, and assured me he would be my doctor for the evening. I clung to that moment of compassion, desperate to fill the overwhelming sense of loneliness.

I squinted, hoping to find him again in a white lab coat, but he was nowhere in sight. The nurse by my bedside remained stoic and cold. Without acknowledging me, she forcibly sat me up and turned around to search for my clothes. Stunned and dizzy, I watched my surroundings spin, struggling to steady myself. My arms, still tied to the bed, felt numb.

As my hospital gown slipped down my shoulders, exposing my breasts, fear gripped me. With no curtains drawn, I worried someone might walk by and see me. I asked the nurse to pull up my gown or close the curtain, but she ignored me. Frustration and shame overwhelmed me as I noticed a phlebotomist lingering nearby, ogling at me with a sinister grin. I bowed my head, letting my hair fall forward in a futile attempt to shield myself.

After what felt like an eternity, the nurse finally turned around and shut the curtain, sparing me another second of feeling like a sideshow oddity.

A Look at the Worst Time in My life While Enjoying the Best Time in my life.

A Look at the Worst Time in My life While Enjoying the Best Time in my life.

The above post was originally written 2007 as a journaling exercise while in therapy. At the time it was written, a full 10 years had passed since the original event. Enough time had passed that I was able to begin unpacking the unresolved traumas. I was able understanding things with some level of clarity. This was my first introduction to therapy. I participated in a DBT skills group and tried out EMDR. These interventions were helpful in reducing the exquisitely painful nature of the traumas that overwhelmed me. Progress in that first decade meant learning to create what Marsha linehan calls ” Creating a Life Worth Living”

At first I just needed to “get unstuck”.

Getting Unstuck has meant learning to Dealing with Reality

more work remains in dealing with autism

What would I like to tell the younger me?

I know what you are thinking: not exactly the most creative thing to say. However it is very true. There was a reality that I lived for many years that was indeed unacceptable. It was a life with unending pain and misery that was beyond my capacity to handle. I wanted the pain to go away, I saw no choice, I just wanted the hurt to end. However, I did hold on. I learned to create a life I felt was worth living.

As Marsha Linehan describes above, it did get better. Beyond the hurt that overwhelmed me and the unlivable reality of my daily life, there was a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. Over time, I continued to grow well beyond the limits of my misery a legacy of neurobiology and environment. I went well beyond creating a life worth living & live every day in gratitude.

-

-

- The suicidal person is like someone trapped in a small room with high, stark white walls but no lights or windows. The room is hot, humid, and excruciatingly painful. The individual searches for a door out to a life worth living, but cannot Scratching and clawing on the walls do no good. Screaming and banging bring no help. Falling to the door and trying to shut down and feel nothing give no relief. Praying to God and all the saints one knows brings no salvation. The room is so painful that enduring it for even a moment longer appears impossible; any exit will do. The only door out the individual can nd is the door of suicide. The urge to open it is great indeed.

- The suicidal person is like someone trapped in a small room with high, stark white walls but no lights or windows. The room is hot, humid, and excruciatingly painful. The individual searches for a door out to a life worth living, but cannot Scratching and clawing on the walls do no good. Screaming and banging bring no help. Falling to the door and trying to shut down and feel nothing give no relief. Praying to God and all the saints one knows brings no salvation. The room is so painful that enduring it for even a moment longer appears impossible; any exit will do. The only door out the individual can nd is the door of suicide. The urge to open it is great indeed.

-

– (Linehan, et al, 2012)

- “DON’T SAY SUICIDE IS SELFISH: SUICIDE IS NOT A CHOICE” (Akerman 2015): “those struggling with thoughts of suicide need all of us to understand that they don’t want to be in a place of overwhelming pain. They would typically rather be alive and living without that pain, and viewing their condition and behaviors as a choice only adds to the burden they already carry. It takes practice to empathize with someone who feels like death is a better option than life in a given moment. One has to be able to refrain from judgment, understand that suicide is not a personal weakness or someone’s “fault,” and recognize that suicide is often a product of mental health and environmental variables that we don’t fully comprehend

- SUICIDE IS AN ATTENTION-SEEKING ACT: “‘I actually kept begging for help. I remember doing that a lot. I would stand before my family and teachers, and I’d just be like “I need someone to fix me. I don’t know what’s wrong with me”. And no one knew what was wrong with me – they just assumed I was an attention-seeker . . . No matter what I said, the more I tried to say I needed help, they didn’t care. It was like, “No, you’re just wanting attention. We’re going to ignore you”. (Team, 2021)

- TALKING TO SOMEONE ABOUT SUICIDAL THOUGHTS MAY TRIGGER THEM TO ACT: “‘ I do not want to minimize the fact that suicide, and even the broader topic of death, are difficult to talk about for a lot of people. It is indeed uncomfortable to talk about suicide. But knowledge is power, and there are misconceptions that contribute to these feelings, mainly the idea that talking about suicide will cause a person to kill themselves (or give them the idea)” (Team, 2021)

- THINKING ABOUT SUICIDE DOES NOT MEAN SOMEONE IS MENTALLY ILL “Some of the most harmful misconceptions about people with mental health conditions are that they are weak or have a character flaw,” says Shanette Smith, LMFT, a lead clinical program developer at Sharp Mesa Vista Hospital. “If we lead from a place of compassion, and use language that reflects that compassion, we will create a safer place to encourage others to seek help.” Stigma is pervasive and severely undermines people’s willingness to talk about their suicidal thoughts and feelings.t lessens the likelihood that people will seek and engage with professional support, especially if they have had negative experiences.” (Murphy, 2021)

References

Ackerman, J. (2019, November 15). Don’t Say It’s Selfish: Suicide Is Not a Choice. Www.nationwidechildrens.org. https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/family-resources-education/700childrens/2019/11/suicide-is-not-a-choice

Dolezal, L. (2022). The horizons of chronic shame. Human Studies (4), 739-759.

Holmes, A. (2015). That which cannot be shared: on the politics of shame. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 29(3), 415-423.Yale University Press.

Harris-Perry, M..V. (2011) Sister Citizen: Shame, stereotypes and Black women in America. Yale University Press.

Linehan, M. M., & Lungu, A. (2012). Compassion, wisdom, and suicidal clients. Wisdom and compassion in psychotherapy: Deepening mindfulness in clinical practice, 205-220.

Linehan, M. M. (1997). Validation and Psychotherapy. In A. Bohard & L. Greenber (Eds.) Empathy Reconsidered: New Directions in Psychothrerapy. Washington DC: AC 352-392.

Murphy, M. (2021, May 26). Does talking about suicide make someone more likely to commit suicide? University of Nevada, Reno. https://www.unr.edu/nevada-today/news/2021/atp-normalize-talking-about-suicide

Team, T. H. N. (2021, September 8). Removing the Stigma Around Suicide | Sharp HealthCare. Www.sharp.com. https://www.sharp.com/health-news/use-these-phrases-to-lessen-the-stigma-of-suicide

A Look at the Worst Time in My life While Enjoying the Best Time in my life.

A Look at the Worst Time in My life While Enjoying the Best Time in my life.